Theoretical wave propagation

Explore seismic wave propagation using normal modes, NACT, and advanced theoretical models for global tomography.

A Brief Introduction to Normal Mode Seismology

All seismic motions occurring within a spherically symmetric body (which the Earth nearly is) can fully be described by a superposition of the natural modes of oscillation of that body - namely, the body’s normal modes. Features of any physical object that violate spherical symmetry, such as rotation, ellipticity, and lateral heterogeneity in material properties, introduce “splitting” of the modes. In other words, a given normal mode in a non-spherically symmetric medium oscillates at a number of different nearby frequencies; this number is proportional to the inherent spatial length-scale of the mode, and the magnitude of the frequency differences is a function of the level of heterogeneity. Furthermore, modes oscillating at similar frequencies can exchange energy, which process is called “coupling”.

Because the Earth is nearly spherically symmetric, the strength of lateral heterogeneity typically sampled by seismic waves of interest in global seismology is weak. As a result, its effects can be approximated by considering small perturbations to the properties of the spherically symmetric Earth, and neglecting terms that depend on quantities smaller than this small perturbation (i.e. higher order terms). This approximation is equivalent to considering traveling waves that are only scattered once by heterogeneity, and is called the Born Approximation.

Non-linear Asymptotic Coupling Theory

Since 1995, we have been developing global mantle tomographic models based on full waveform seismograms and a theoretical mode-coupling approach called non-linear asymptotic coupling theory, as first applied by Xiang-Dong Li and Barbara Romanowicz (Li and Tanimoto, 1993; Li and Romanowicz, 1995).

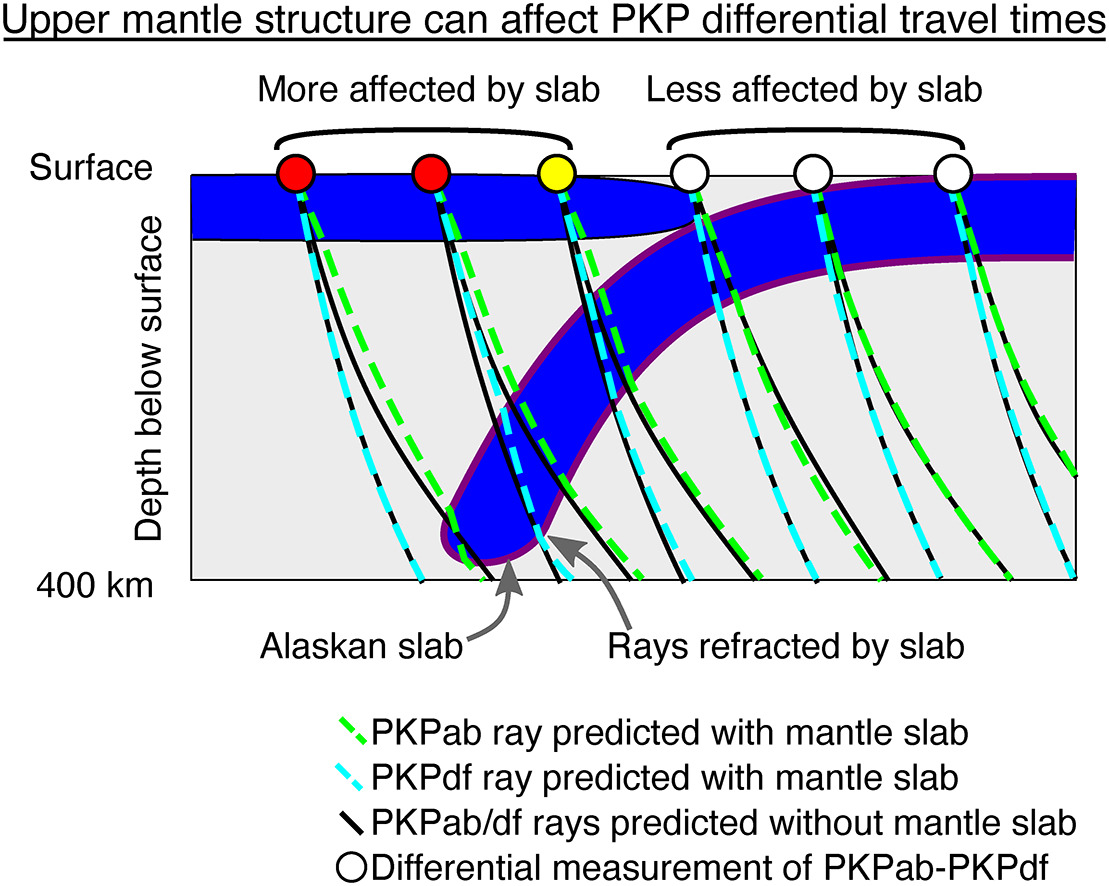

Within the context of the aforedescribed Born Approximation, we can calculate the frequency shifts produced by lateral heterogeneity. With this knowledge, we can also compute the extent of coupling between modes proximate in frequency. Instead of accounting for coupling between all possible mode pairs (which entails large computational costs), global seismologists have typically only taken into account coupling between modes that share the same radial order. If we consider seismic waves traveling between two points on the Earth, this further approximation is equivalent to ignoring all but the average structure along the great circle path joining the points. Appropriately enough, this approximation is dubbed the “great circle” or “path average” approximation (PAVA; Woodhouse and Dziewonski, 1984).

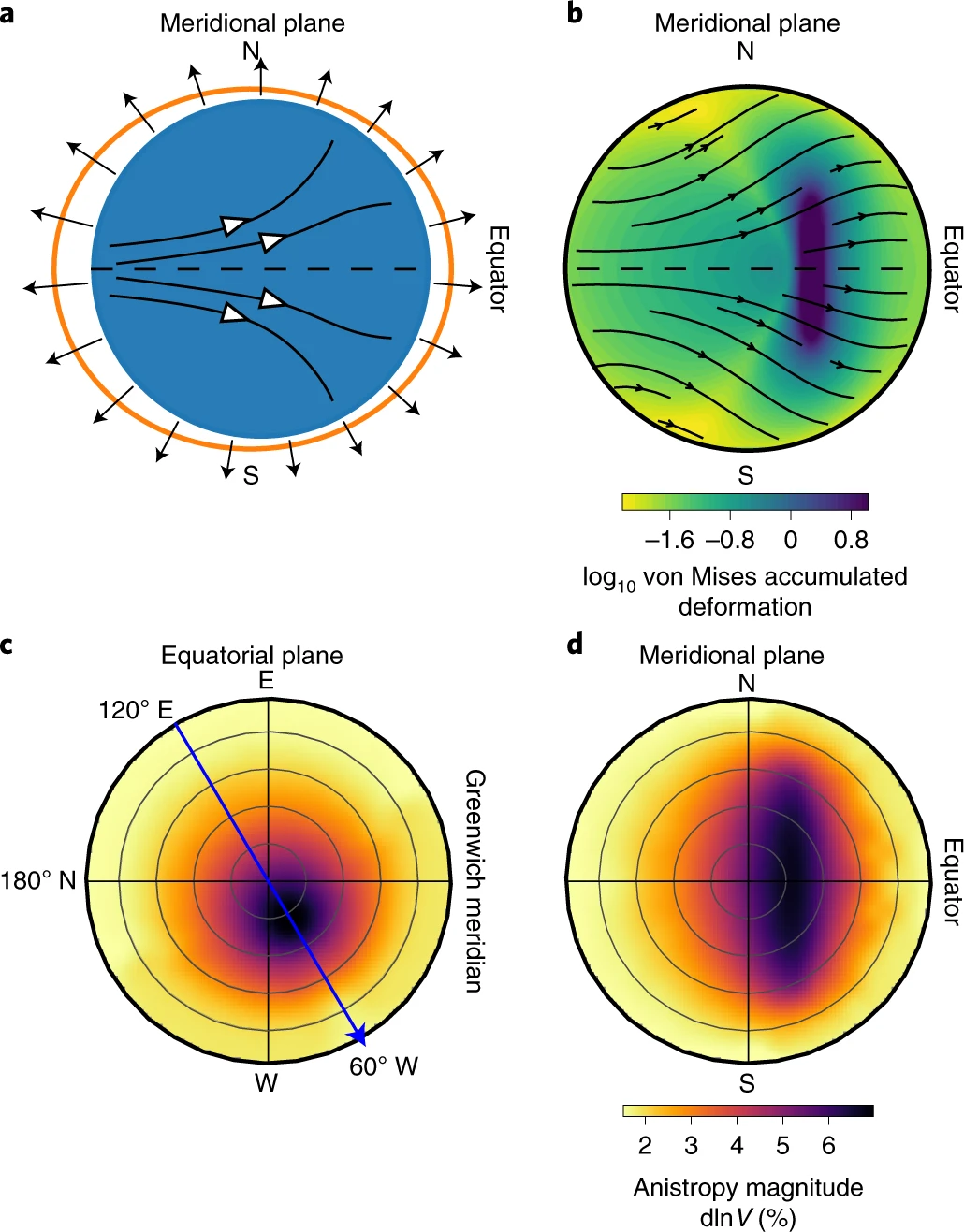

In non-linear asymptotic coupling theory (NACT, Li and Romanowicz, 1995), we also account for coupling between modes that do not share the same radial order. In terms of travelling waves, this practice is equivalent to considering not only average structure, but also variations in material properties along the great circle path joining a source and receiver. Equivalently, we can say that NACT allows us to “follow” the seismic waves as they dive into the Earth and emerge back at the surface (see the figure to the right). Because of this advantage, NACT makes possible waveform modeling of surface wave overtones as well as body waves.

The Born Approximation

During the past few years, we have also been developing ways of implementing the full Born Approximation, and applying it to global and regional tomography.

Let us first consider the computational costs of accounting for coupling between each pair of modes, for each source-receiver path, as described above. Since the number of modes of frequency less than the corner frequency of the seismogram of interest is proportional to the square of the wavenumber (length-scale) of the mode, we see that the total number of necessary calculations is proportional to l4.

Instead, let us find inspiration in the fact that the Born Approximation is a single-scatterer approximation. From the point of view of the scatterer, a seismic wavefield propagates from the source to it, and upon interaction, continues on to the receiver. It turns out that the effect of this individual scatterer on the observed seismic waveform is described by a convolution of the source-to-scatterer forward wavefield with the received-to-scatterer backward wavefield. Since each wavefield can be fully represented by normal mode summation, we see that for a given scatterer, the number of computations increases as l2 (Capdeville, 2005).

Using this scatterer-based approach, we have developed codes to sum up the effect of each individual scatterer, allowing a far more computationally efficient implementation of the Born Approximation.

The Coupled Spectral Element Method

Finite element methods, which involve solving the weak formulation of the equation of motion within each volume element of a discretized Earth, offer us a means for calculating the displacement in an arbitrary 3D medium. However, as the frequency of interest increases and the scale of the heterogeneity decreases, one needs to consider ever smaller volume elements, resulting in greater computational costs.

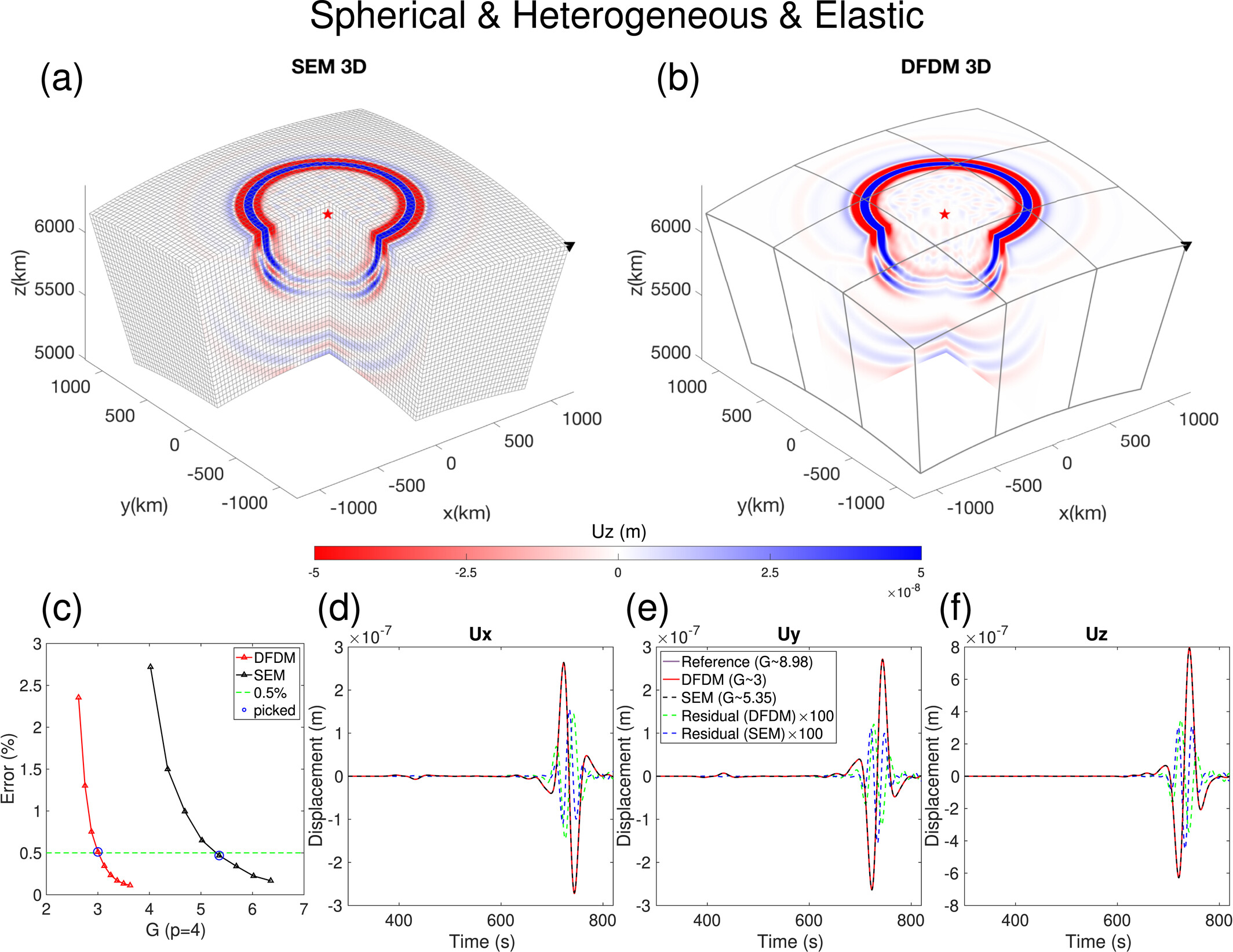

The spectral element method (SEM) represents both the medium and the wavefield using low-degree Gauss-Lobato-Legendre polynomials, which increases accuracy - since by increasing the order of the polynomial, one can essentially approximate the wavefield arbitrarily closely - and makes possible the use of larger volume elements. Additionally, the use of Gauss-Lobato-Legendre polynomials also simplifies the algorith for solving the wave equation within each element (e.g. Maday and Patera, 1989).

Since we might not always be interested in accounting for the 3D structure of every portion of the Earth, we can think about using normal mode summation in some regions of the Earth and full 3D SEM in others. Capdeville et al. (2002) have developed a way of coupling the modal solution in one spherically symmetric region of the Earth to the numerical wavefield in another, via a Dirichlet-to-Neumann operator which transforms displacement boundary conditions to ones specifying tractions. This coupled SEM (cSEM) makes possible faster computations.